Summary Background

A SUMMARY OF THE ECONOMIC CONDITIONS IN NORTHWEST MICHIGAN

The CEDS summary background information for the northwest Michigan region describes the current economic conditions and helps present a clear understanding of the relevant economic issues. The data presented in the summary background and appendices is important to connect with the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis discussed later in the CEDS.

Total Population

309,563

Networks Northwest

Unemployment Rate

4.2%

Networks Northwest

High School Graduate or Higher

92.85%

Networks Northwest

Civilian Labor Force

147,805

Networks Northwest

HOUSING

Housing is one of our most basic human needs: where we live affects our health, wealth, access to opportunity and quality of life. Without safe, adequate, affordable housing, individuals face serious challenges to meeting their basic needs. When area residents struggle to meet their basic housing needs impacts are felt throughout the community. On our roads, residents commute further between work and home, in our schools, we struggle with declining enrollment as young families leave our communities to find more affordable housing; and in our businesses, which lose customers when residents have less disposable income due to high housing and transportation costs.

Shortages of affordable housing exist throughout the Northwest region of Michigan, and because of this, many families live farther from jobs, schools, and shopping to find homes they can afford. Housing shortages also occur when developers focus on building large single-family homes which have been profitable for developers in the past but do not meet the needs of the community. Focusing on building single-family homes limits the potential for building other types of housing in the region such as rental units, mixed use developments, smaller houses for senior citizens, and housing for those with disabilities.

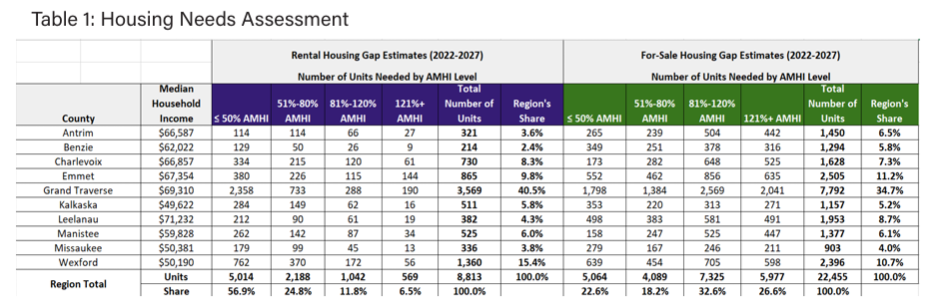

Finally, costs are being driven up by suppliers unable to keep pace with the demand and by an unprecedented increase in construction costs of land, labor and materials, particularly in high growth areas of Michigan. To help address the persistent problem of the housing shortage, the region is served by numerous public agencies, nonprofits, and private sector interests. In particular, the non-profit organization Housing North provides outreach, messaging and communications tools; advocates for policies support housing development opportunities in rural Michigan; and works with partners to develop new tools and funding options for housing. The organization’s 2023 Housing Needs Assessment for the region takes into account the demographics, economics and housing supply of the region, along with the input of area stakeholders and major employers, and estimates the housing gaps of the region between 2022 and 2027 (Table1).

WORKFORCE TALENT

Capacity, Attraction & Retention

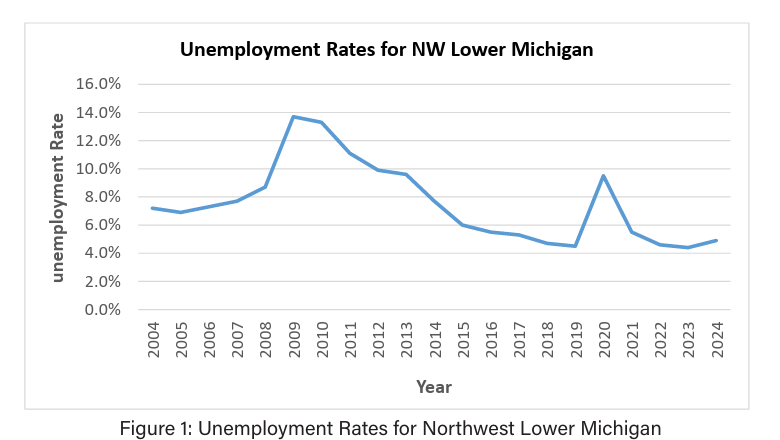

The first significant spike in unemployment since the great recession occurred in 2020 (9.5%), due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unemployment fell significantly in the years following through 2023, with a slight increase in 2024 (4.9%).

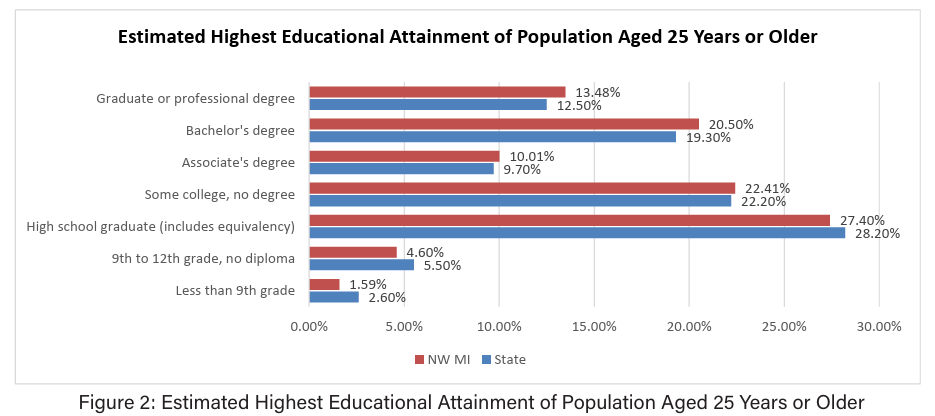

The region’s population aged 25 years or older has slightly higher level of post-secondary educational attainment, on average, compared to the state as a whole (Figure 2). Approximately 44% of the region’s population (aged 25 years or older) an Associates Degree or higher, compared to 41.5% at the state level. 22.4% of the region’s population has “Some College, No Degree” as their highest level of education, and 27.4% have achieved a high school diploma. While these estimates may fit with the overall distribution of projected job demand by educational attainment, it is not sufficient for high-wage, high-demand jobs. In addition, the category “Some College, No Degree” does not accurately reflect the shorter-term credentials, such as apprenticeships and trade certifications that may be held by local talent.

According to the 2024 Annual Planning Information and Workforce Analysis Report for the Northwest Michigan Region by the Michigan Center for Data and Analytics, the region had roughly one-third of its population between ages 25 to 54. The region was older than the statewide average, with more individuals ages 55 and older.

The region’s population increased by 5.2 percent between 2012 and 2022. This was a gain of 15,700 residents, showing a total population of 315,200. The growth rate in the Northwest area was the second highest of all Michigan Works! areas. However, this growth can primarily be attributed to people in retirement and near-retirement age groups (over age 55). The population under 19 years of age has continued to decrease, indicating continued future decreases of working-age populations.

CHILD CARE

Networks Northwest’s 2024 Regional Child Care Plan (click photo to left) states that the regional child care system continues to not have sufficient capacity to meet the needs of families with young children. It is estimated that the region needs full time care for roughly 2,600 young children (0-4 years old). The unmet need is greatest for infants and toddlers (0-2 years old). The most common barriers reported by parents and other caregivers are availability of care and cost of care.

Additionally, most regional employers report one or more impacts of the child care shortage include employees missing work, employees being distracted or reducing scheduled hours. Many regional employers also report employees who have left positions or turned down job or promotion offers because of child care issues. Statewide, Michigan’s child care shortage costs the state economy $2.9B annually in lost earnings, productivity and revenue.

The plan identified 14 identified solutions addressing one or more of the root causes of the child care provider shortage, achieving improvement in these areas: access to care when and where families need it, affordability so that families can afford to pay for care, and quality so that children are cared for in a safe, nurturing, and developmentally appropriate environment.

NATURAL HAZARD MITIGATION

Between 2021 and 2025, Networks Northwest assisted all ten counties and two of the three indigenous tribes in the region with completing updated natural hazard mitigation plans. A current, FEMA approved and locally adopted 5-year hazard mitigation plan is required by a community to apply for certain types of non-emergency disaster assistance grants offered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

The plans include an analysis of the history and vulnerability of each county to multiple types of natural hazards, including public health emergencies (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) and invasive species. Each plan also contains mitigation strategies to address one or more type of hazard. Strategies can generally be grouped into the categories of: Communication, Coordination and Preparation; Infrastructure; Land Use Planning & Regulations; Public Health & Assistance; Natural Resources Management; and Wildfire Prevention. Each complete plan can be accessed at: Networks Northwest Hazard Mitigation Website

For almost all counties, the most frequently occurring natural hazard event is wildfire on state or federally-owned lands, followed by severe winter weather, thunderstorms/high winds, and hailstorms. Inland flooding concerns were expressed for every county, and many of the mitigation strategies address the need for improvement of dams, roads, and stormwater infrastructure. One example of a damaging flash flood event occurred in August 2021 in Antrim County, where Alden Highway (M-88) was completely washed out near Comfort Road.

Dams that have a “high hazard potential” rating (if the dam were to fail) are located in Antrim, Grand Traverse, Leelanau, and Manistee counties. The counties with Lake Michigan shoreline (Emmet, Charlevoix, Antrim, Grand Traverse, Leelanau, Benzie and Manistee) have mitigation strategies to address the coastline erosion and flooding associated with fluctuating lake levels, which occurred between 2019 and 2021, and are expected to reoccur in the future. Other shoreline hazards include dangerous currents, waterspout, and seiche.

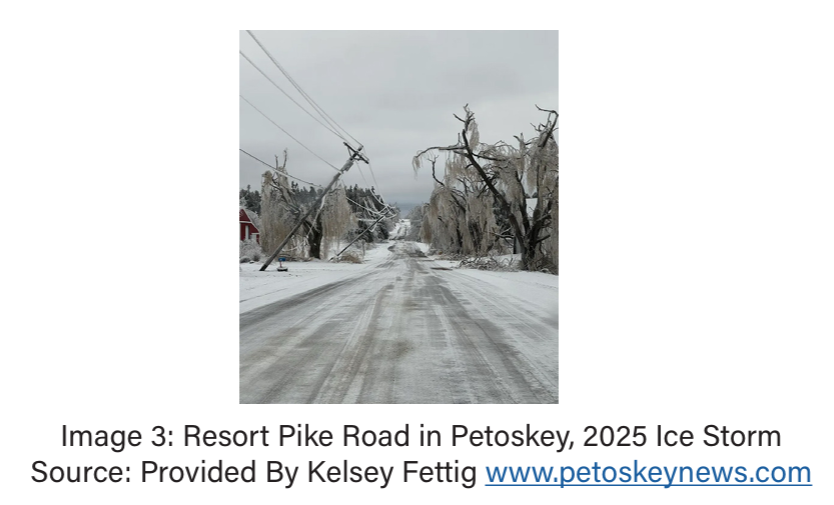

The spring 2025 ice storm is an example of a recent severe winter weather event of unprecedented scale that destroyed much of the power grid in Emmet county, and parts of Charlevoix and Antrim counties. The event resulted in a Governor-declared state of emergency. Many homeowers remained without power for several weeks in below-freezing temperatures and relied upon the services of community shelters. Forested areas suffered severe tree damage and many property owners incurred losses to their homes or businesses.

Additionally, wildfire is a particular natural hazard concern in parts of Wexford, Manistee, Kalkaska, and Grand Traverse counties, due to the concentrations of pine forest in those areas.

OUTDOOR RECREATION

Northwest Michigan offers a wide variety of outdoor recreation opportunities, with non-motorized and motorized trail systems, ski resorts, agritourism venues, parks, and plentiful lakes, streams, and forests. The Outdoor Recreation Economic Impact Study for Northwest Michigan (2024, click here for overview) indicates that the region has almost double the concentration of agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting employment than national averages for regions of similar size, as well as higher than average concentrations in manufacturing, construction, retail, and arts, entertainment, & recreation, indicating a strong, blue-collar base and foundation for Outdoor Economy employment. The Outdoor Economy employs an estimated 4,712 workers, or 3% of the labor force in the region and contributed 1.15 billion to Gross Regional Product in 2022. Furthermore, jobs in this sector grew by 9% over 10 years (2002 to 2022) within the region.

Survey responses of over 200 regional outdoor industry businesses revealed that the majority of outdoor recreation-based businesses in northwest Michigan are growing, and 96% reported their sales were increasing or stable. 72% reported they were planning on additional hiring in the next three years. By far, the biggest challenge experienced by these businesses is the lack of available talent and/or well-trained workforce.

The study listed the following key opportunities to pursue:

- Connect new and existing businesses to financial and technical assistance resources

- Facilitate professional networking for additional business-to-business sales

- Plan for growth in the shoulder seasons

- Support trail expansions and connections, targeting complementary small business development

- Market underutilized areas and welcome diverse visitors

- Educate communities about conservation and responsible use of outdoor assets

- Develop infrastructure to spur growth

- Steward the region’s natural character and protect outdoor assets

- Focus on business attraction and growth in these sectors: marine services; bikes and e-bikes; ORV and SxS rentals; outfitters, guide, and transportation/shuttle services; and e-boating.

- Also, while not an outdoor recreation issue in isolation, outdoor industry advocates should work with regional partners to ensure an adequate supply of workforce housing is available to support the local talent pool and the diverse businesses that make up the region’s Outdoor Economy.

INFRASTRUCTURE

Infrastructure is the fundamental facilities and systems serving a country, state, county, township, or city and is necessary for its economy to function. Infrastructure includes roads, bridges, dams, rail systems, aviation, transit, water, sewer, and solid waste systems, energy, broadband, and educational facilities. Infrastructure is the foundation of our everyday lives and touches all parts of how we live, work and play in Michigan. It is the backbone of Michigan’s economy.

Our transportation system (roads, bridges, transit, rail, etc.) allows Michiganders to travel to work every day, or up north for summer weekends by the lake. Water systems deliver drinking water to our homes, communities, and businesses. School buildings provide a safe place for our children to learn. Broadband service access promotes successful business activity, employment opportunities and remote learning. Sewer and treatment systems protect our neighborhoods from floods, and our lakes, rivers, and beaches from raw sewage, E. coli and other toxins.

Most of Michigan’s infrastructure is old, outdated and in need of repair. In older Michigan cities, some systems date back to the late 1800s. For close to a decade now the state has suffered from a poor economy, resulting in Michigan under investing in infrastructure. However, recent investments have included $3.5 billion in bond funding from the “Rebuilding Michigan Program” and $4.7 billion from the “Building Michigan Together” plan. Michigan is also set to receive $11 billion for much needed infrastructure projects through 2026 from the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

As of the 2020 U.S. Census, the Traverse City area reached the population threshold of 50,000 people required to become a metropolitan planning organization (MPO) – a status that provides an influx of more federal dollars for road projects and the ability for local governments and agencies to come together on one board to make regional transportation decisions. An MPO is charged by the federal government with overseeing regional transportation planning on a “3-C” basis: comprehensive, continuing, and cooperative. The MPO Policy Board works together to create a long-range transportation plan (LRTP), a document that outlines transportation projects 20 or more years out. That plan is updated every five years and has a required public participation component. The MPO also develops a short-term transportation improvement plan (TIP). That plan, which is approved by the governor, typically looks just four years out and is updated annually.

Much of the following summaries and data were retrieved from the “2023 Report Card for Michigan’s Infrastructure”, prepared by the American Society of Civil Engineers, Michigan Section, as well as from the Michigan Transportation Asset Management Council.

ROADS

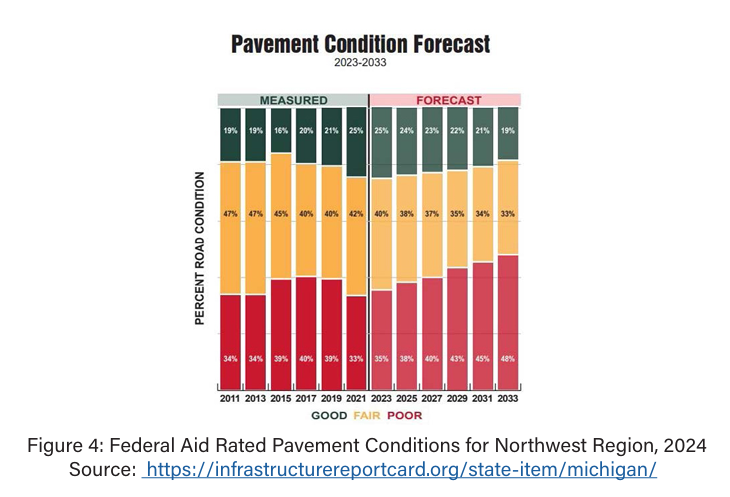

The Michigan Transportation Asset Management Council (TAMC) tracks pavement condition on the state’s roadways under state and local jurisdiction. Their pavement condition forecasting system showed that statewide, for 2021, 25% of pavement was in good condition, with 45% in fair condition, and 33% in poor condition. That’s an improvement from 20% good in 2017 and reduction down from 40% poor in that same year.

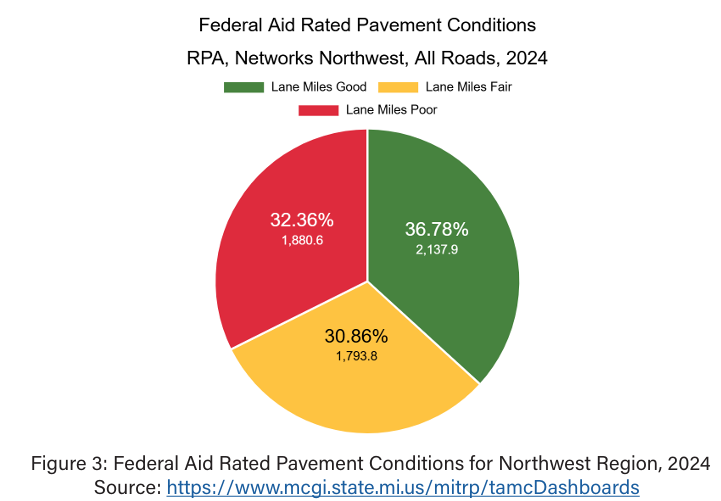

Based on a 2024 assessment, 32.36% of Northern Michigan’s Federal Aid paved roads are rated in poor condition, 30.86% are rated in fair condition, and 36.78% are rated in good condition.

The state’s pavement tracking system estimates a continual decline in conditions between curbs using current funding models. Current dedicated funding, fee revenue, and estimated gas tax amounts show progress on pavement condition stalling and reversing. The percentage of paved roads in poor condition is fore-casted to rise from 33 percent in 2023 to 48 percent in 2033.

Governor Whitmer’s 2020 “Rebuilding Michigan Program” included $3.5 billion of one-time bond financing, accelerating major highway projects on state Trunklines over a 4-year period. In November 2021, the President signed into law the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), aka Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. This federal legislation will provide Michigan approximately $336 million more per year (2022-2026) than under the previous transportation bill (FAST Act). Unfortunately, inflation and supply issues are undermining most of the increase as dollars are not going as far for transportation improvements.

To erase decades of underinvestment and meet future needs, decision-makers should increase dedicated funding for roads, re-tool fee models, prioritize traffic safety, and improve resilience to worsening environmental threats.

BRIDGES

Michigan’s over 11,000 bridges are critical connections in our surface transportation system, providing crossings over waterways, roads and railroads. A deteriorating and inadequate highway transportation system costs Michigan motorists billions of dollars every year in wasted time and fuel, injuries and fatalities caused by traffic crashes, as well as wear and tear on their vehicles. In 2022, 34% of Michigan bridges were in good condition – a drop from 43.5% in 2018. Deck areas in good condition dropped from 37.2% in 2018 to 28.9% in 2022. While fair condition bridges have stayed stable on count terms, 65.6% of bridge deck area is now in fair condition, compared to 55.4% in 2018. Poor condition bridges have held between 5% and 6% in the last four years, however they are disproportionate by ownership. 6% of MDOT-owned bridges and 14 percent of locally owned bridges were in poor condition in 2021.

Table 2: Bridges by Condition Rating in Northwest MI Counties, 2024

Source: https://www.mcgi.state.mi.us/mitrp/tamcDashboardsre…

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law of 2021 will provide $563 million to Michigan from FY 2022-2026 for bridge replacements, rehabilitations, and preservation programs in Michigan. These formula funds will allow state and local governments to move forward with numerous bridge projects. However, these funds will not be enough to address the decline in bridge condition shown above nor make significant ground on the backlog of bridge work.

Michigan’s Mobility 2045 long-range transportation plan, published in 2021, placed annual bridge spending at $157 million for state-owned structures and $75 million for those locally owned. Raising Michigan bridges to its own performance would cost $216 million more per year for state bridges and $164 million for the local counterparts. That $381 million total annual need sums to $9.5 billion over Michigan’s 25-year transportation planning window.

DAMS

Michigan’s approximately 2,600 dams support water supply, flood control irrigation, hydro-power, economic development, and recreation. Approximately 75% of the state’s dams are privately owned, with others owned by municipalities, public utilities, the state, or federal government. According to the National Inventory of Dams, there are 161 “high” hazard potential dams in the state. (Hazard potential is not an indication of the dam’s condition, but an indication for the potential for loss of life and property damage if the dam were to fail.) Approximately 65% of those high hazard dams are rated as being in satisfactory condition; 19% as fair; 8% as poor; 6% as unrated; and 2% as unsatisfactory.

There are a total of 54 dams in the northwest Michigan region, with an average age of 94.3 years. A total of ten (10) of those dams are rated with a high hazard potential if they were to fail. (Table 3). The two high hazard potential dams in Manistee and Wexford counties are hydropower dams operated by Consumer’s Energy (CE). The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) operating licenses for these dams expire within the next decade. CE, as the owner and licensee, must file with the FERC a notice of intent to apply for a new license at least five years before the existing license expires. In 2022, CE began a detailed review of its river hydro operations to understand the financial, societal, and environmental impact of the three options available to them: pursue relicensing of the river hydros; decommission and remove the river hydros; or to sell the river hydros and transfer the licenses to a new buyer.

Michigan’s dam safety program budget was increased after dam failures at Edenville and Sanford in 2020. But new resources are needed to improve the overall condition of dams across the state. The Michigan 21st Century Infrastructure Commission Report (2017) cited a need for $225 million over the next 20 years to manage aging dams.

Table 3: Dams in Northwest Michigan

Source: National Inventory of Dams - https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil/#/

RAIL SYSTEMS

Michigan’s rail system has approximately 4,000 miles of track, 84% of which is owned and operated by 27 private railroad companies, with the remainder owned by the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT). Rail is used to move 17% of freight in Michigan, transporting $194 billion annually in agricultural products, chemicals, large equipment, and other commodities.

Three passenger rail services operate between Chicago and Michigan’s cities, but the state is disconnected from high-ridership routes that connect Boston, New York, and Washington. Passage of the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law directed new funds, leveraged by state and private investment, for safety and service upgrades.

Active rail systems are located within eight of the ten counties in the region, connecting the communities of Petoskey, Boyne Falls, Mancelona, Kalkaska, Cadillac, Manton, Harrietta, Traverse City, Kingsley, McBain, and Manistee.

AVIATION

The region has two airports classified as “small non-hub airports” (Pellston Regional Airport and Cherry Capital Airport) and numerous “local basic” and “unclassified” airports throughout the region. The bulk of capital funding improvements to the aviation system are provided with federal Airport Improvement Program (AIP) funding through the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The conditions and overall safety of the aeronautical infrastructure has been well monitored and maintained through an asset management concept described in the Michigan Aviation System Plan.

TRANSIT SYSTEMS

While a majority of Michigan’s residents have access to some form of public transportation, the reliability and availability of these services to many areas are inadequate, and some rural systems are unable to adequately meet transit demands. All ten counties in the region have some form of transit service through public transit agencies or specialized providers. Transit may be limited in some areas in both terms of the service area and/or the individuals served. Federal funds for rural services are awarded to Michigan and programmed by the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT).

Public Transit Agencies in Northwest Lower Michigan:

- Antrim County Transportation

- Bay Area Transportation Authority

- Benzie Bus

- Cadillac/Wexford Transit Authority

- Charlevoix County Transit

- Kalkaska Public Transit Authority

- Manistee County Transportation

- Straits Regional Ride (serves Emmet County)

DRINKING WATER

Most of the infrastructure within the State of Michigan’s community water supply systems (CWS) are over 50 years old and a significant portion is approaching 100 years of service life. The state has an $860 million to $1.1 billion annual gap in water infrastructure needs compiled from decades of deferred maintenance and lack of knowledge on asset conditions. The Flint water crisis placed a national spotlight on the impacts of deteriorating infrastructure, fragmented decision-making, and severe underinvestment in water infrastructure. Many other Michigan CWS need critical infrastructure improvements. Drinking water upgrades have jump-started thanks to regulatory advancements on lead and copper, requirements for asset management planning, and recent influxes of funding for projects including replacement of over 27,000 lead service lines. Long-term, sustainable funding sources are needed to drive continued success.

All twelve (12) of the incorporated cities in the northwest Michigan region provide a CWS, as well as many of the incorporated villages and some townships.

STORM WATER SYSTEMS

Stormwater management systems in Michigan provide flood protection, impact water quality, improve agricultural production, and extend the service life of roads. Stormwater threats from intense weather are growing. Total annual precipitation has increased by approximately 14% in the Great Lakes Region since 1900, but the amount of precipitation falling in the heaviest 1% of storms has increased by 35% since 1951. There have been 7 federal disaster declarations in Michigan related to severe storms and dam breaks in the past 10 years. Both public and private storm sewer systems do not have the capacity to safely convey water from those extreme water events. Recent implementation of asset management programs identifies greater needs and regulatory constraints. County road commissions own 75% of Michigan roadways for example, but funding for their drainage systems is capped by the State Drain Code at only half of necessary stormwater investment needed.

SOLID WASTE SYSTEMS

Overall, Michigan’s collection, transfer and disposal infrastructure is robust, with approximately 26 years of landfill disposal capacity remaining. Municipal solid waste (MSW) disposed of in Michigan totaled approximately 17 million tons in 2021, a slight decline from previous years. Daily per capita waste generation is approximately 7.32 pounds, nearly double the national average. Michigan is beginning to actively shift its overall solid waste philosophy toward a sustainable materials management approach to create economic opportunities through waste diversion, beneficial reuse, and recycling programs.

The state’s estimated residential recycling rate was 19% in 2021, up from 14% in 2016. While this is encouraging, the recycling rate is still much lower than the national average of 32%. Michigan is 20aiming for a 30% recycling rate by 2030 and, since 2019, the number of households with available curbside recycling and drop-off sites has nearly doubled.

The State of Michigan has called for an update to local government’s Materials Management Plans (f.k.a. Solid Waste Plans) to be completed by July of 2027. The update is the result of amendments to Part 115, Solid Waste Management, of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act, 1994 PA 451, as amended. The updated plans will focus on sustainable materials management, such as recycling and composting, instead of primarily disposal. The plans will also document existing and new infrastructure; define the needs, goals and opportunities for materials management and facilities; and apply criteria for the siting of all facilities, such as landfills, transfer stations, or composting facilities.

ENERGY

Michigan’s energy systems generally meet current needs. The status is threatened by increasing energy dependence and demand for high service reliability coupled with aging infrastructure, lack of investment to preserve function, exposure to physical and cyber threats, congestion, and dependence on externally sourced fossil and nuclear fuels. Continued renewal of infrastructure, hardening of communications, and innovative smart grid technology use are needed to limit outages and economic impacts. Improving grid-related outage statistics, avoiding pipeline-related failures, and overcoming regulatory/economic/policy barriers are critical to future system performance. Natural gas utility service is limited in northern Michigan. The majority of the rural communities rely on individual propane fuel for heating, or another source such as electric, wood or geothermal. Table 4 lists the utility providers for electric and gas service in the region.

BROADBAND

Today, the success of a state has become dependent on how well it is connected to the global economy and how those connections are leveraged to improve the quality of life for its residents, the sustainability and growth of its businesses, the delivery of services by its institutions, and the overall economic development of its communities. Access to affordable broadband, or high-speed Internet, is a necessity in our professional, personal and social lives.

In 2021 Governor Gretchen Whitmer issued Executive Directive 2021-2 to establish the Michigan High-Speed Internet Office (MIHI) within the Michigan Department of Labor and Opportunity to coordinate investments made into broadband infrastructure and its utilization. In November 2021, MIHI released an Update to the Michigan Broadband Roadmap.

The MIHI office provides the following insights into Michigan’s broadband landscape:

- Michigan has the 20th lowest broadband adoption rate among other states and territories. An estimated 1.24 million Michigan households struggle with Internet connectivity and are on the wrong side of the Digital Divide

- The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated tele-working, and that is not expected to slow down. It is estimated that 56% of the U.S. workforce holds a job that is compatible (at least partially) with remote work, and 25-30% of the workforce will be working from home one or more days per week after the pandemic. Lack of broadband impairs residential and commercial development in many areas of Michigan, including those that have typically been defined as “vacation” properties, tourist destinations, and other smaller rural areas and towns.

- Having broadband provides households with an estimated $1,850 annual economic benefit.

- Statewide, teleworkers save $363 million in car maintenance and fuel annually

- Broadband access can increase home values by an average of 3.1 percent

- Tele-medicine adds an estimated $522,000 to rural economics and reduces hospitalizations

- It is estimated that one percentage point increase in broadband access could create or save about 12,000 jobs statewide

- Small businesses with websites have higher annual revenue than those without

- In a study of manufacturers, 40% stated they were able to add new customers and 57% realized cost savings because of their broadband connections.

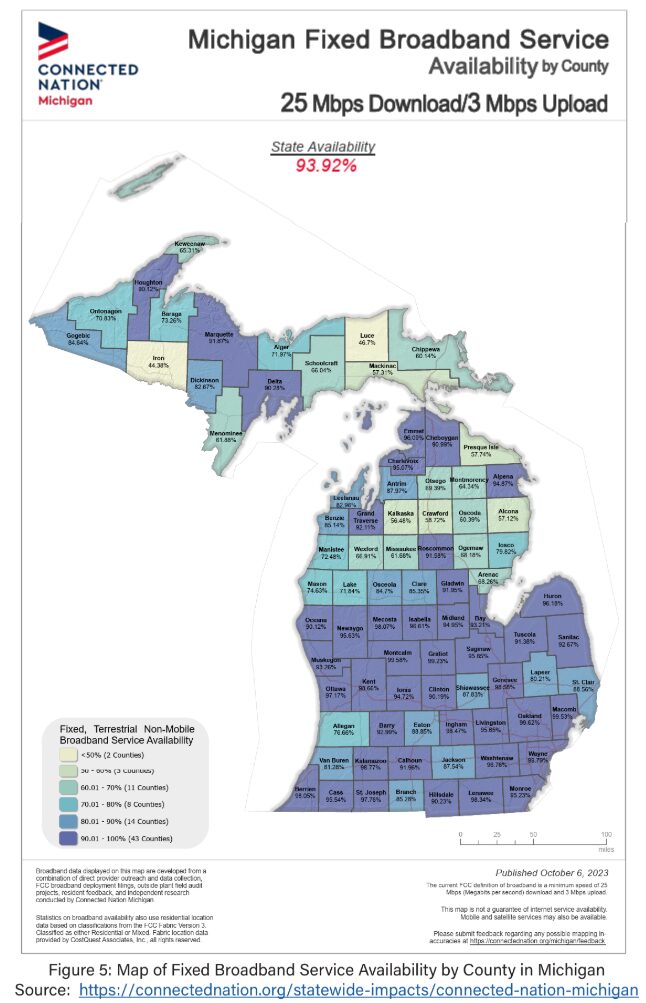

The following map shows the estimated availability of basic broadband (as of 2023). The service availability varies across the northwest Michigan region, with Emmet, Charlevoix and Grand Traverse counties having the most service availability, and Kalkaska, Missaukee and Wexford counties having the least.

EDUCATIONAL FACILITIES

The condition of Michigan’s K-12 education facilities varies widely both across the state, and within individual regions and districts. Michigan’s schools maintain adequate overall capacity, although suburban schools in areas experiencing the heaviest population housing pressure, have been expanding. Based on the statewide declining enrollment of students, the capacity of Michigan schools will continue to be generally adequate. As the population of Michigan remains stable, school enrollment projections are largely predicted by the birth rates in the state. Based on an analysis of birth rates for the last 20 years, the rate of births appears to continue to slowly decline in Michigan, mirroring national trends.

Overall, these institutions have made progress in rightsizing for leveling off enrollment and infrastructure investment shows positive trends. The state spent almost $2 billion on school capital expenditures during the 2020-21 school year, up from $1.7 billion and $1.4 billion in the previous two years. Per pupil facility spending in Michigan now roughly equals the national average of $1,376 per pupil, but much of recent investment comes from one-time increases that expired in 2024. Decision makers should direct predictable, dedicated infrastructure spending to schools, especially because the state is home to many buildings constructed 50+ years ago. Select systems at school facilities have seen upgrades to preserve functionality, but layouts often don’t reflect the teaching needs of 21st century learners.

Northwest Lower Michigan hosts two community college campuses: Northwestern Michigan College in Traverse City and North Central Michigan College in Petoskey. While Northwestern Michigan College partners with Central Michigan University, Ferris State University, Davenport University and Davenport University to offer various services and programs, the region lacks its own four-year university.

Organizations in Northwest Lower Michigan offer a multitude of trade education opportunities across multiple industries to high school to adult aged residents. Organizations such as the colleges above and Career and Technical Education programs hosted by school districts offer the opportunity for trade education in careers such as electrician, welders, and nursing assistants among others. Further opportunities are provided through Northwest Michigan Works! Apprenticeships that upskills employees and recruits new talent to fill gaps and Adult Education that provides educational opportunities for all adults.